But Kinsella's book is altogether different. The author has taken great pains to make this a text that even those with a limited interest in history can digest quite easily. Simply put, Kinsella has researched all the men from South Dublin who died in World War One, and collected the information together in this book. But this is much more than just an ordinary reference book, Out of the Dark is a detailed patchwork of interrelated stories, based on a place-centered pattern. This clever structure enables us to see how whole communities were effected by the war.

Each chapter begins with a geographical description of the place where the soldiers grew up - its contours, its rivers, its landscape - adding a sense of realism and rootedness that seems to highlight, all the more, that these were Irish soldiers, Dublin men, who went away to war. Merging history and geography together in this way, cleverly reminds us who these soldiers were, and fixes them to a place that still exists. They are not just lost in memory, assigned to some ancient battle long forgotten. No, they belonged to Kilternan, Dundrum, Rathmines, Carrickmines and Foxrock etc. places that Dubliners are so familiar with in our day to day lives, and as such, cannot so easily be forgotten. I, for one, will never see these places in quite the same way again.

|

| Donald Lockart Fletcher from Shankill, who died tragically during training. |

Yet, it does even more than that: it moves laterally through families, shining a light on the lives of those who were left behind, the long forgotten fiancee, mother, father, brother, whose lives were also inevitably touched by the huge losses in the 1914-1918 war.

Kinsella deftly makes connections between families too, noting uncanny twists of fate and coincidences that wouldn't be out of place in a work of fiction. Consider the story of local boys, Joseph Plunkett and his close childhood friend, Kenneth O'Morchoe, which features in the chapter on Kilternan. In the 1916 Rising, they came to face eachother in Kilmanham jail, the former facing execution, the latter in charge of the firing squad. There are varying versions of how the story played out, but Kinsella's research finally uncovers the truth of things - but you will have to read the book to find out what happened next.

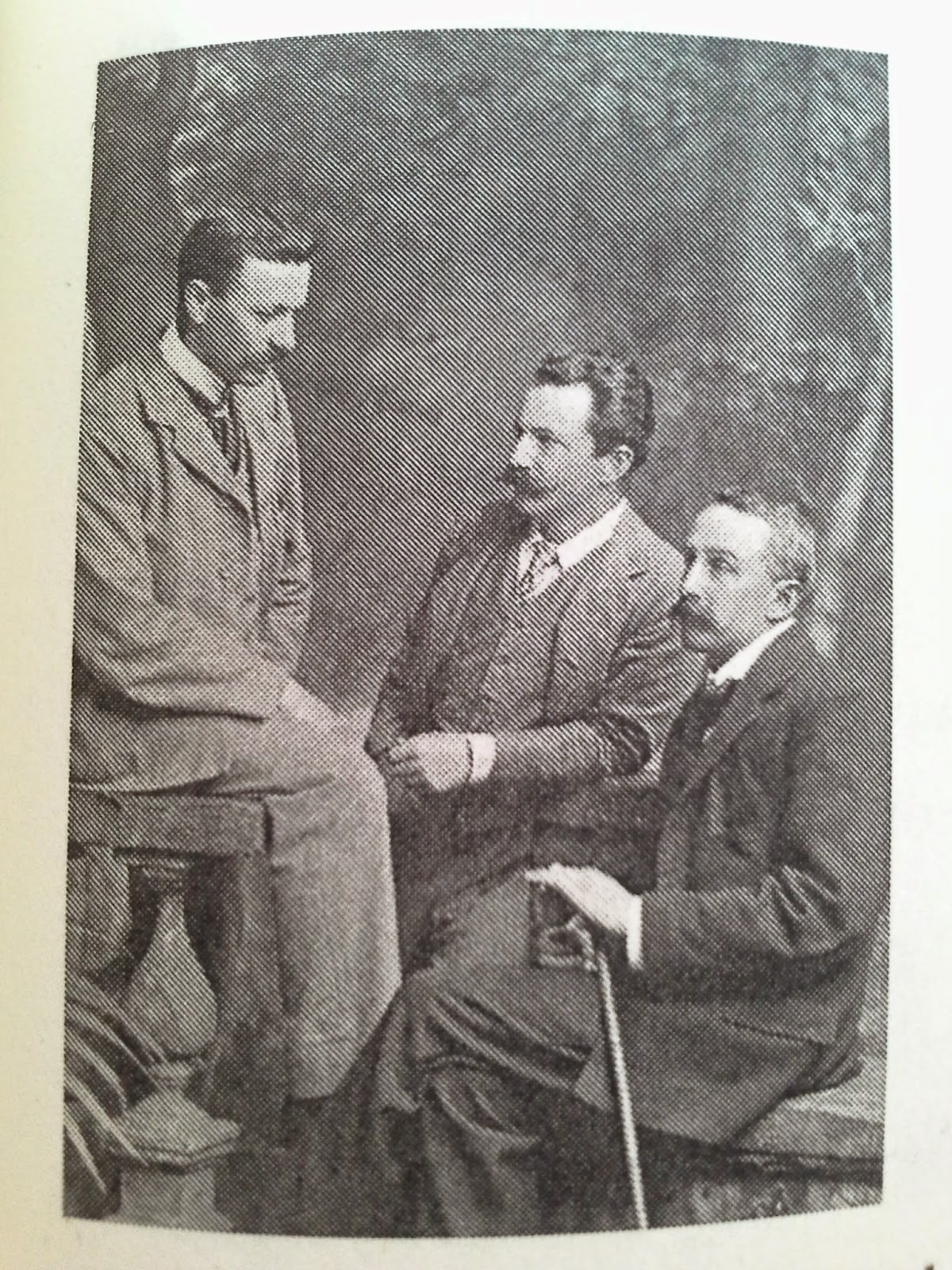

|

| Members of the Findlater family who lost two sons in WWI |

The book is dotted with poetry too, giving a philosphical edge to the information and something for us to quietly ponder. The greats are all here, Owen, Ledwidge etc., but there are other, unknown poets also, friends of fallen soldiers, who, like, L.A.G. Strong, could only voice their deep felt emotion through poetic verse.

Ken Kinsella's book is for anyone who has an interest in families, history, genealogy, The Great War, geography and poetry - in short, it is for everyone. It would make a great Christmas present, especially in this centenary year of the war's commencement. I am very excited about this book, and not just because it contains information about some of the soldiers that I am researching for my War Stories project, but because it is a mammoth piece of social history and research. It tells a story that needed to be told, and in return, needs to be read. I know of at least two people who will be getting this book in their (rather large) Christmas stocking this year. Do you?

By Michelle Burrowes