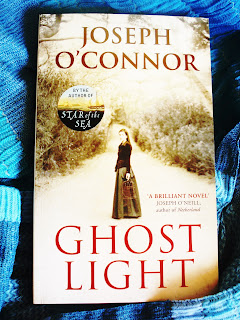

It was a sunny afternoon in Dublin, and I had just stumbled from watching a masterclass given by Maxim Vengerov to some very talented young violinists. With strains of Sibelius still echoing through my head, I wandered by a book shop on Dawson Street and saw Min Kym's autobiography in the window. The striking black hardback was jacketed in vibrant teal, with the silhouette of a curvaceous violin cut out in the center. I thought the image intriguing. I had to have it.

It was a sunny afternoon in Dublin, and I had just stumbled from watching a masterclass given by Maxim Vengerov to some very talented young violinists. With strains of Sibelius still echoing through my head, I wandered by a book shop on Dawson Street and saw Min Kym's autobiography in the window. The striking black hardback was jacketed in vibrant teal, with the silhouette of a curvaceous violin cut out in the center. I thought the image intriguing. I had to have it.

To be honest, I hadn't even heard of Min Kym before I bought the book, but having spent a few days with her voice ringing through my head, and listening to the CD the accompanies the book, I feel that I know her well enough now. As an autobiographer, Kym manages to walk that tight-rope between story telling and truth that this genre relies upon.

Indeed there were times that I felt that Kym too easily ran from responsibility, blaming all life's problems on her parents for making her too submissive, which resulted in her Stradivarius violin being stolen, her resulting depression and anorexia. But in a way, I think that this was part of the book's charm; her imperfections as a protagonist made her seem more human. When you read between the pages, you can see that Min was a very determined little girl, every such 'master' musician has to be selfish with their time, and egotistical to a point. The young Min was well able to challenge her Korean teacher who lacked the skill to teach her. Determination and confidence were inherent in the young progeny. What was so tragic was how an opportunistic crime sent her into a tail-spin and that confident little girl got lost. The hard truth was that it wasn't just a violin that was stolen in the café that day.

Indeed there were times that I felt that Kym too easily ran from responsibility, blaming all life's problems on her parents for making her too submissive, which resulted in her Stradivarius violin being stolen, her resulting depression and anorexia. But in a way, I think that this was part of the book's charm; her imperfections as a protagonist made her seem more human. When you read between the pages, you can see that Min was a very determined little girl, every such 'master' musician has to be selfish with their time, and egotistical to a point. The young Min was well able to challenge her Korean teacher who lacked the skill to teach her. Determination and confidence were inherent in the young progeny. What was so tragic was how an opportunistic crime sent her into a tail-spin and that confident little girl got lost. The hard truth was that it wasn't just a violin that was stolen in the café that day.

The reader can empathise with Min's loss because in the chapters leading up to the theft, she explains simplistically and poetically what a violin means to a player. She describes it as her child, a female baby, another limb, her teacher, but is not content with any of these similes. What is clear, is her utter anguish at the violin's loss and the tragic thing is that this book is a tragedy. Though the violin was found, the instrument was never returned to her to keep, insurance companies put pay to that, and to this day, it remains locked away in a bank vault, suffering the silent fate of so many of the world's most valuable instruments. And this is something that the book forces you to consider: how is it that musicians can no longer afford to own and play these very old and treasured instruments? Surely they do not belong in the dark?

It is because Kym repeated personifies the Strad that we are horrified by its ultimate fate. She compares her suffering to it, saying how they are both imprisoned now. This was the most moving part of the book for me. Her beautiful instrument, which 'glowed' for her, now never sees the light of day. Surely it should be where the public can enjoy it, someplace where it is not just be a musical equivalent of stocks and bonds.

It is because Kym repeated personifies the Strad that we are horrified by its ultimate fate. She compares her suffering to it, saying how they are both imprisoned now. This was the most moving part of the book for me. Her beautiful instrument, which 'glowed' for her, now never sees the light of day. Surely it should be where the public can enjoy it, someplace where it is not just be a musical equivalent of stocks and bonds.

Yet, experts argue that these hugely expensive violins are not as special as we imagine them to be. In a recent study, listeners prefered the sound of modern violins, when comparing them to old instruments while blindfolded. This suggests that the myth of the master luthier and his violins is just that, a myth. That supports what any sensible person already knows, that these old violins are ridiculously over-priced, but it is to the benefit of banks and investors that the myth continues. And after all, there is an intangible romance about violins, whether be their aesthetic design, or evocative sound, that keeps us spellbound.

For me, every violin is a promise of something truly beautiful, in the hands of the right player that is. And Kym's book publishers have knowingly used the image of the violin on the book's cover to entice readers like me. The really clever bit is that the image is a void, a cut-out, the violin itself, missing from the image, and as such mirrors perfectly the book's narrative.

For me, every violin is a promise of something truly beautiful, in the hands of the right player that is. And Kym's book publishers have knowingly used the image of the violin on the book's cover to entice readers like me. The really clever bit is that the image is a void, a cut-out, the violin itself, missing from the image, and as such mirrors perfectly the book's narrative.

'Isn't it beautiful?' the book shop sales assistant said to me when I presented it to her at the counter. 'I saw it this morning myself', she added, 'and I had to get a copy. We ought not to judge a book by its cover I know. Let me wrap that separately,' And with that she enfolded it in soft paper so as not to tear the jacket, and placed it lovingly into a bag on top of my other purchases, just as if it were a real violin! So I was not the only one guilty of loving this book cover, of loving violins, of loving a myth. And with this book you get all that and a good story.

|

| Check out my Etsy Bookshop! |

.jpeg)

.jpeg)